Thoughts on what the CDC YRBS data means for social media, teens, and mental health

This piece is the first in a series that takes an in-depth look at what we can learn from recent and long-term data about teen mental health.

UPDATE 2/20/24: The original post featured two images of the same chart that used incorrect data. The corrected charts and images have been updated below. Our original analysis remains. To learn more and to read an explanation of the error, please read this post by Will Rinehart.

On February 13, The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) released “The Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2011–2021,” a summary of the latest findings from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS). The CDC has conducted the YRBS since 1990. What is most worrying about this release is the mental health decline of adolescent Americans, especially teenage girls.

For 2021, 42% of high school students said that they had persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness. Among girls, the number was 57% percent, up from 47% in 2019.

These shocking numbers have spurred a small blizzard of analyses, as they should. A popular theory is that social media, particularly the introduction of Instagram as well as the Like button, maps the timeline of increasing poor mental health indicators like suicides, suicide ideation, and feelings of sadness and hopelessness.

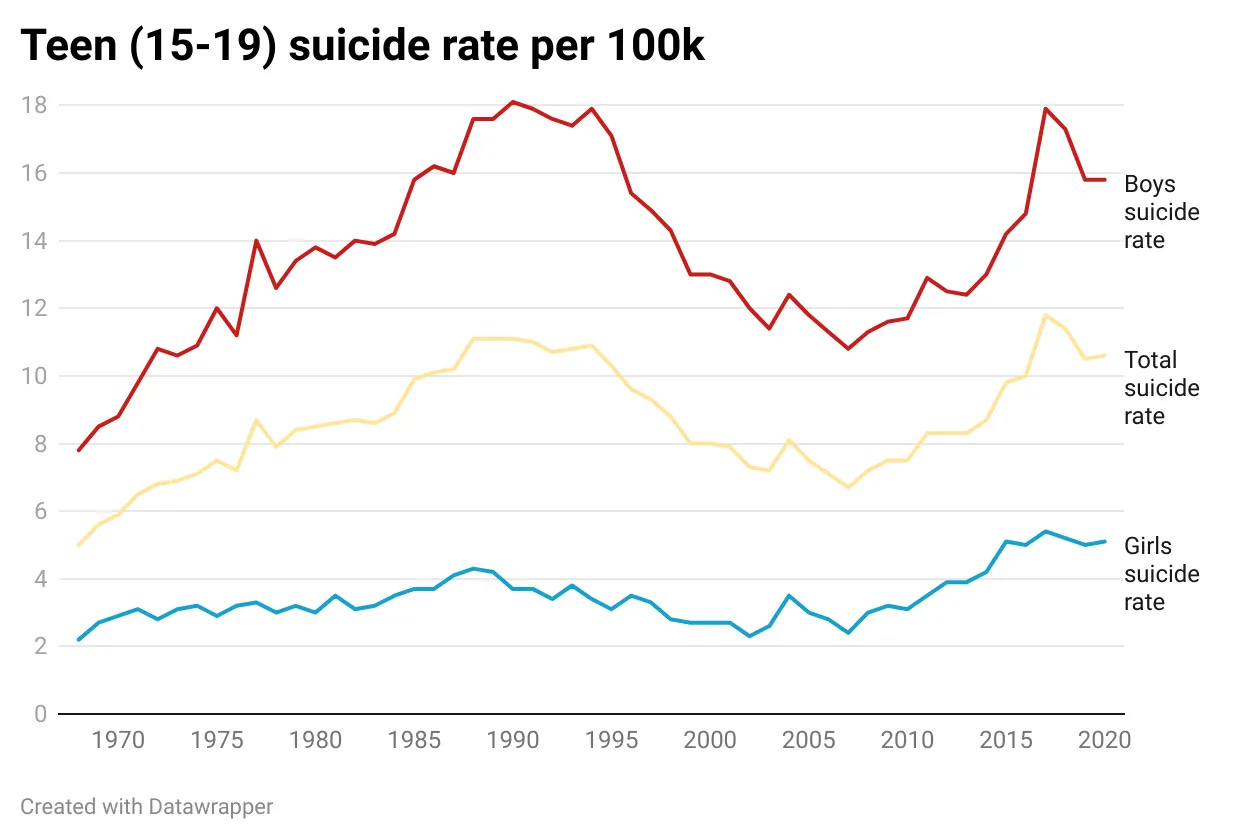

Missing from most analyses is a look at the trends that stretch to a time before we had social media. When you begin back in the late 1960s, when the CDC began collecting data, it becomes clear that the US has already survived at least one great wave of poor teen mental health.

CORRECTED CHART

It took just over 20 years for the US suicide rate to go from its low point in 1968 to its high point in 1990. And it took just under 20 years for that to drop back down to its low of 2007. Now suicides and sadness are on their way back up, which leads to a hard question for public policymakers.

Is what we are seeing a trend or a cycle?

Trends are different from cycles. Cycles revert towards the mean. They fluctuate around an average point over years. Trends, on the other hand, are something new. They mark a change that is out of the normal cycle.

All of the data suggest teen mental health is on a downswing. The tough part, which this series is dedicated to, is splitting apart the trends and the cycles. To make sure we don’t make a misstep in public policy, we need to discuss the possibility that this data could be a cycle.

1990: The beginning of YRBS and the peak of teen suicides

The YRBS is the national survey that comes from the broader Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS). The YRBSS is “a system of surveys” conducted every two years. It includes a national school-based CDC survey as well as local surveys sponsored by state, territorial, and tribal governments that are administered by local education and health agencies.

The YRBSS was first put into the field in 1990 to better track the leading causes of mortality and morbidity among young adults. At the time, it was widely recognized that suicide rates among teens were rising, as the figure below helps to illustrate, but there was little understanding why. The system was set up to better understand the problem.

CORRECTED CHART

By 1987, a New York Times article detailed just how confounded experts were about the rise in teen suicides: “James Mercy of the CDC said researchers have no explanation for the trends. Experts have speculated that increasing family breakups, drug abuse, dwindling job and educational opportunities and the growing availability of guns could be factors.”

But also in 1987, researchers were suggesting that another possible risk factor was simply exposure to the idea of suicide or contagion. A report from scientists at the CDC noted that,

Direct exposure may occur through a friend or classmate's suicide; indirect exposure to suicide may also occur through news reports, books, movies, or discussions. . . . Apparent clusters of suicides have been reported among young persons in many areas of the United States, but the number of such clusters that occur is not known.

The YRBSS was set up just as suicides were peaking. Over the next two decades, teen suicides would be halved from a rate of 11.1 per 100,000 to 5.3 per 100,000. What was a national concern receded.

The 2010s: A new trend in teen mental health or a cycle?

Around 2007 to 2009 all of the surveys on teen mental health showed that teens were doing the best in decades. Suicides reached an absolute low in the data in 2007 with 5.3 per 100k. Consistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness among teens reached a low in 2009 as did contemplation of suicide.

The chart below stacks all of the major surveys together on the same timeline.

Between 2007 to 2009, teen mental health began to worsen. Suicide rates went up as did contemplations of suicide. But the real kicker is that in the last five years, incidences of teens feeling hopeless or consistently sad have marched up a steep incline.

This has been especially true among girls. Overall, more girls express feelings of sadness and contemplate suicide than boys at any point in time. The chart below breaks out the differences between males and females.

What exactly is the trend we are seeing here?

In an exploratory study of the all the survey data, available on Github, we subjected the nine datasets mentioned above to trend analyses. The nine sets included rates of suicide deaths, feeling sad or hopeless, and contemplating suicide as expressed in the total rate, the boys’ rate, and the girls’ rate. This analysis estimates the probability that a trend has changed. While much more is needed to truly understand what is happening here, each of the nine markers showed slightly different potential trends.

Here is our read of the data.

First off, the declines in suicide around 1999 is the biggest event by far. Both girls and boys saw significant declines in suicide around the turn of the century, but it was especially true for boys. Girls, interestingly enough, also saw major improvements in 1987. For them, that year ranks alongside 1999 as the biggest moment of renewed positivity.

Little is known about what went right in 1987 or 1999.

Second, and more subtly, feelings of sadness and hopelessness seemed to have a trend change around 2015. This was true for boys, girls, and a combination of the two. In an Atlantic article on this topic Jonathan Haidt ballparked the moment of change for teens between 2011 and 2015. Our first cut at the data suggests we should be looking towards the very end of that estimate. As such, it could mean that neither the 2009 introduction of the Like button on Facebook nor the introduction of Instagram in 2010 are the culprits of teen ills.

What this means

Although the recent data suggests a trend, at least part of this change could come from a cycle. We intend to dig deeper into the data and the research. Still, this first cut of the data should give some pause to monocausal theories. There is a lot that is happening all at once.

It is a shame that this data is only collected every other year. The next YRBS survey is going out to teenagers soon, but we won’t know how well teens are doing today until 2025. Everyone, especially teens, would benefit from knowing earlier about what is happening. More timely data would also better inform policymakers’ well-meaning, though sometimes misguided, efforts to help teens.

Evidence-based policymaking requires evidence.

See

https://theshoresofacademia.blogspot.com/2019/11/youth-suicide-rise-articles-index.html

for a series of analysis I've done on CDC data.

The big graph "Teen (15-19) suicide rate per 100k" at the start remains wrong.

For pre-1999 data, you use ages 15-19 data, correctly so per your title; for 1999-2020 data, you incorrectly use ages 13-19 data.

Obviously this produces a huge rates drop in 1999 and all subsequent years; in reality ages 15-19 suicide in boys has recently reached similar peak levels to those of early 1990s and girls surpassed them.